[Prepared for Memorial Tribute to Dr. Anderson Thompson, August 17, 2019, DuSable Museum, Chicago, IL]

Anderson Thompson (Weheme Peri Kush) is a metronome by which we measure African rhythms in time and space. His work on historical memory influences everyone he knew, taught and/or organized with. His reading, teaching and writing practices, delinked from vulgar careerism and shaped by often thankless work of connecting people and ideas, mapped pathways for so many of us. From when we met until his transition, I imitated his practice more closely than anyone’s: Search. Collect. Read. See human experiences as connected, not fragmented. Curate. Teach. Connect others. Move simply. Inject circumspectly. Learn. Defend the African way.

In the pre-digital era, securing a copy of Baba Andy’s 1975 article, Developing an African Historiographyfrom Black Books BulletinVolume 3 was a physical rite of passage. He and the Kemetic Institute travelled to Columbus, Ohio for ASCAC’s Fall 1991 Midwest Regional, my first chance to meet the legendary collective that had so shaped our movement’s trajectory. His ubiquitous baseball cap pulled low on his head, Baba Andy had slipped into the room at Columbus Alternative High School as Valethia Watkins, Troy Allen (Maa Kheru) and I discussed African-Centered education. Afterward, I excitedly introduced myself and commented on the book he had under his arm, an original hardback copy of The Rebirth of African Civilizations. We fell into the rite-of-passage talk of dedicated men of print. That night, I got my first of a quarter century of intergenerational mouth-to-ear transmissions from his encyclopedic mind and, as I would learn later, my first cold blooded vetting to join his apogee circle of nationalist bibliomaniacs that included John Henrik Clarke, Yosef ben Jochannan, Larry Obadele Williams (Maa Kheru), Kweku Larry Crowe, Adisa Makilani, Conrad Worrill, Asa G. Hilliard III (Maa Kheru) and a few rabid others.

Baba Andy paused that Friday night to say “come with me: There’s someone I want you to meet,” introducing me to Nzinga Ratibisha Heru (Maa Kheru), then newly-elected second President of ASCAC. In fact, it was Anderson Thompson who literally led me by the hand to members of the Kemetic Institute, beginning with the towering Jacob Carruthers (Maa Kheru). We had joined the Association through Baba Moriba Kelsey and Columbus’ Afrikan Center for Study and Worship. Baba Andy had done what he always did: Expanded the network of Pan Africanists, Black Nationalists and African people, connecting us to common, collective liberation work. His name remains a shibboleth, a password: If you knew him, doors could open from Kemet to Sudan to Brazil, from the hardest core street level organizers and scholars to the doors of gymnasiums and gates of ball fields to the highest levels of the Library of Congress. Anderson Thompson, scribbled notes in hand, peripatetic purveyor of place, was highly respected among those who know.

From that moment on, I tried my best to observe and model Baba Andy as much or more as anyone. To hear and learn the sources of his thinking and teaching practice, from his connection with educators such as Margaret Burroughs, Barbara Sizemore and so many others. To be tutored in watershed moments in what he, his lifelong Brother Harold Pates, his co-occurring comrade Jake Carruthers and their companions called “The Intellectual Warfare,” from establishing the Association of African Historians, the Afrocentric World Review and the Association of African Educators to feeding N’COBRA, the UNIA-ACL, the Nation of Islam, NPEPAA and so many other formations. You knew he was decamping a enervating libation from his living archive when, glint in eye, he shook his head, said “Brother” with a chuckle, and showed you the lesson.

Whenever we had gathered young people and he was around, I would ask him to join the intergenerational Mbongi, even if he didn’t speak much. As a result, more young people can now speak of hearing him outline and discuss, impromptu and without notes, long comparative intellectual genealogies, annotating as he went. His model remains my model: Never without writing tools, a cache of books and ephemera, and the little slips of paper upon which, his close comrades would often tease, he had written down the history of the entire world. What he worked on worked on him. Steel sharpens steel. The affable and at once piercing command with which John Henrik Clarke discusses his life and work in Wesley Snipes’s A Great and Mighty Walkis made more understandable when we reflect that his intellectual kinsman Andy Thompson had shaped the questions he was being asked and was in the room as he answered.

Like any Jegna, Baba Andy revealed his depth as his students acquired theirs. This had the effect of creating a sense of familiarity that resonated with all of us and likely had the unintended consequence of undervaluing his status as one of the finest thinkers produced during our long sojourn in what he and his comrades call “This Mess.” It is the central reason why I wanted to make sure that we with The Compass published his valedictory commentary on historiography. By then, he’d emptied the equivalent of a library of publications into communities he built with, colleagues he shared with, and the future in the form of his apprentices. We now breathe life into each other and into eternity, attentive and creative toolmakers from the sebayt he left us.

As he said during ASCAC’s historic 1987 Aswan conference and beyond, “all history is about the future.” His spoken and written words, like Monk solos, are masterful narrations of relationships of time and space. His phrases echo in our heads: “The Old Scrappers,” “Nomadic Historiography,” “The Decade of Truth,” and so many more. As non-combatants emerge from hiding places in the academy to pick though random archives to cobble sterile echoes of Black movements, they will eventually stumble upon Anderson Thompson and realize that everything they have written or will ever write is virtually useless. They are never able to capture the essence and purpose of a living tradition. They mistake the little slips of paper for the thing itself.

One of the great honors in my life was to present Baba Andy, the Champion of Kush, with the copy of The Compassthat features his article, lovingly and brilliantly edited by his Kemetic Institute comrades. He smiled as he thumbed the pages. Then for one more Saturday afternoon, he held forth at Communiversity. “We have to be serious now,” he said, “its time for you all to take the next leg.” His room and his words were spare. His mind and spirit were not. I will repeat that glossed repetition of the timeless Sebayt of Ptah Hotep to everyone, as long as I live.

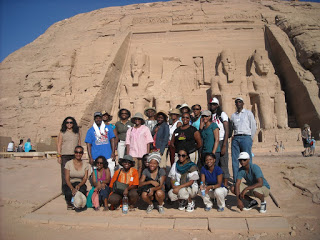

Anderson Thompson will forever be our model for intellectual work. Those few of his annotated books with which I have been entrusted sit here on my desk, fertile and furious physical placeholders signaling his perpetual charge to read, think, teach and connect our people. We have obeyed divine instruction that he physically reside forever in our beloved Nile Valley. His soul, his lifework being found Maa Kheru, rises, eternally, like Ra. Amun is satisfied. Hotep.